In NAIRU We Trust (But Verify)

The RBA has beefed up it's approach to the estimating full employment

The RBA recently released a set of notes on how it estimates and thinks about the NAIRU under a FOI request. Unlike most FOIs, which often seek political headlines about some contentious matters, this request turned up a genuinely interesting set of information.

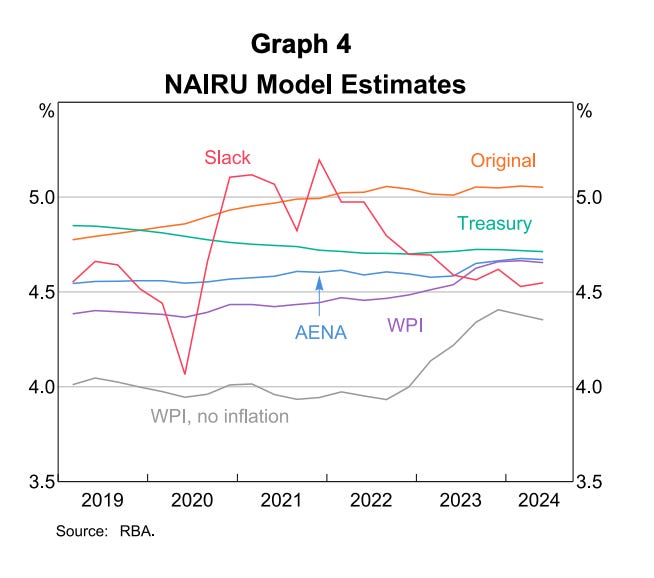

The first thing to note is that, since 2017, when Tom Cusbert published the RBA's original model of the NAIRU, the range of models used by the RBA has proliferated. There are now half a dozen different attempts to measure the level of unemployment consistent with a stable rate of inflation. Interestingly, you can now pick your NAIRU model based on a wide array of factors. Do you want to focus on unit labour costs, or would you prefer the wage price index? Should you explicitly include labour productivity, or would you rather use a wage measure that considers average earnings? There is a wide range of choices available.

A Unanimous Jury

However, despite this array of specifications, my takeaway from the notes is that there is a large degree of agreement between the different modelling approaches.

Importantly, all of them estimate a midpoint for the NAIRU that is well above the current unemployment rate of 3.9%. This is significant because a critical factor influencing economists' estimates of full employment—and thus their policy prescriptions—can vary based on what variables they prioritize.

At a recent flash forum run by the Melbourne Institute, I noticed that the defining difference between the plethora of speakers was their emphasis on different variables when devining the state of the economy.

Some looked at unit labour costs, which are currently growing at a fairly rapid clip, concluding that we are well below the NAIRU. Others focused on the wage price index, whose slower nominal growth indicates a less tight labour market. However the RBA considers NAIRU models with both variables and while the wage price index models produce an estimate slightly lower, around 4.5%, it is still well above the current unemployment rate. So regardless of your preferred wage measure, the case for interest rate cuts from the perspective of full employment in the RBA's mandate is not compelling.

The second thing worth noting is the level of detail in the note. Only a few years ago, the RBA relied on just one model of the unemployment rate. Before that, it is unclear whether it had any formal models updated regularly. Now, not only does it have half a dozen, but these are clearly updated a quarterly basis. The note even breaks down what factors have led to a slight upward revision in the NAIRU, attributing this to a mix of data revisions, new incoming data, and model adjustments. This shows that the RBA is taking its mandate for estimating the NAIRU seriously and devoting considerable resources to the task.

Facing Judgement

The third interesting point is the explicit acknowledgment of judgment when combining model estimates into a final figure. The note indicates that, most recently, the RBA used its judgment to revise down the model estimates by 15 basis points.

Is this non-quantitative judgment providing a more accurate picture of the economy? Who knows! This could be a task for some RBA graduate a decade from now: to go through the archives and evaluate whether judgment improved or degraded the RBA's model estimates of the NAIRU.

For now, this judgment—lowering the NAIRU estimate by 15 basis points—implies that in a standard monetary policy rule, interest rates are being kept about 30 basis points lower than they otherwise would be, based purely on quantitative evidence. Will this subjective judgment lead to better monetary policy? That remains an open question. It would, however, make for a fascinating inquiry during one of the Governor's next public appearances, where she bravely subjects herself to public scrutiny.