In my last post I compared a range of different monetary policy targets to see how they react to a shock to world commodity prices. I found that nominal GDP-targeting performed relatively poorly in the presence of this shock, producing a path for the cash rate that is both volatile and poor at stabilising output and the core inflation rate.

However this result is somewhat unsurprising. Terms of trade shocks have long been known to be nominal GDP-targeting’s Achilles Heel for many years. Most advocates of nominal GDP targeting claim that it is better able to handle supply shocks, a problem we may be seeing more of as climate change creates a more volatile world.

Let's test that hypothesis next

Food for thought

Perhaps the most obvious way in which climate change will affect our economy is by increasing the volatility of food prices. Floods, storms and heat waves are all likely to damage our ability to reliably produce agricultural goods leading to an increased volatility for their prices.

So what happens if we simulate an increase in food prices across the different monetary policy regimes in MARTIN?

These results should seem familiar. In fact they are qualitatively identical to the increase in commodity prices that we modelled in the previous post. This is because MARTIN models the agricultural sector entirely as another export industry. Higher food prices increase the value of agricultural exports, but they are not assumed to affect domestic inflation directly.

Thus a shock to world agricultural prices has a very similar impact to a shock to world commodity prices. They are both essentially a transitory sector-specific terms of trade shock.

This is perhaps a questionable assumption. Food makes up a much larger share of the CPI than iron ore does and I suspect households have a much lower ability to substitute away from it when prices rise.

So against my better judgement I have altered my version of MARTIN to relax this assumption. Specifically, I re-estimated the equation for trimmed-mean inflation to include a term for world agricultural prices. Fortunately this change seems to be both significant (agricultural prices positively affect the core inflation rate) and orthogonal to the other causes of inflation (ie it doesn't radically change the other parameters in the regression).

How does this revised edition of MARTIN model the impact of high food prices on the Australian economy?

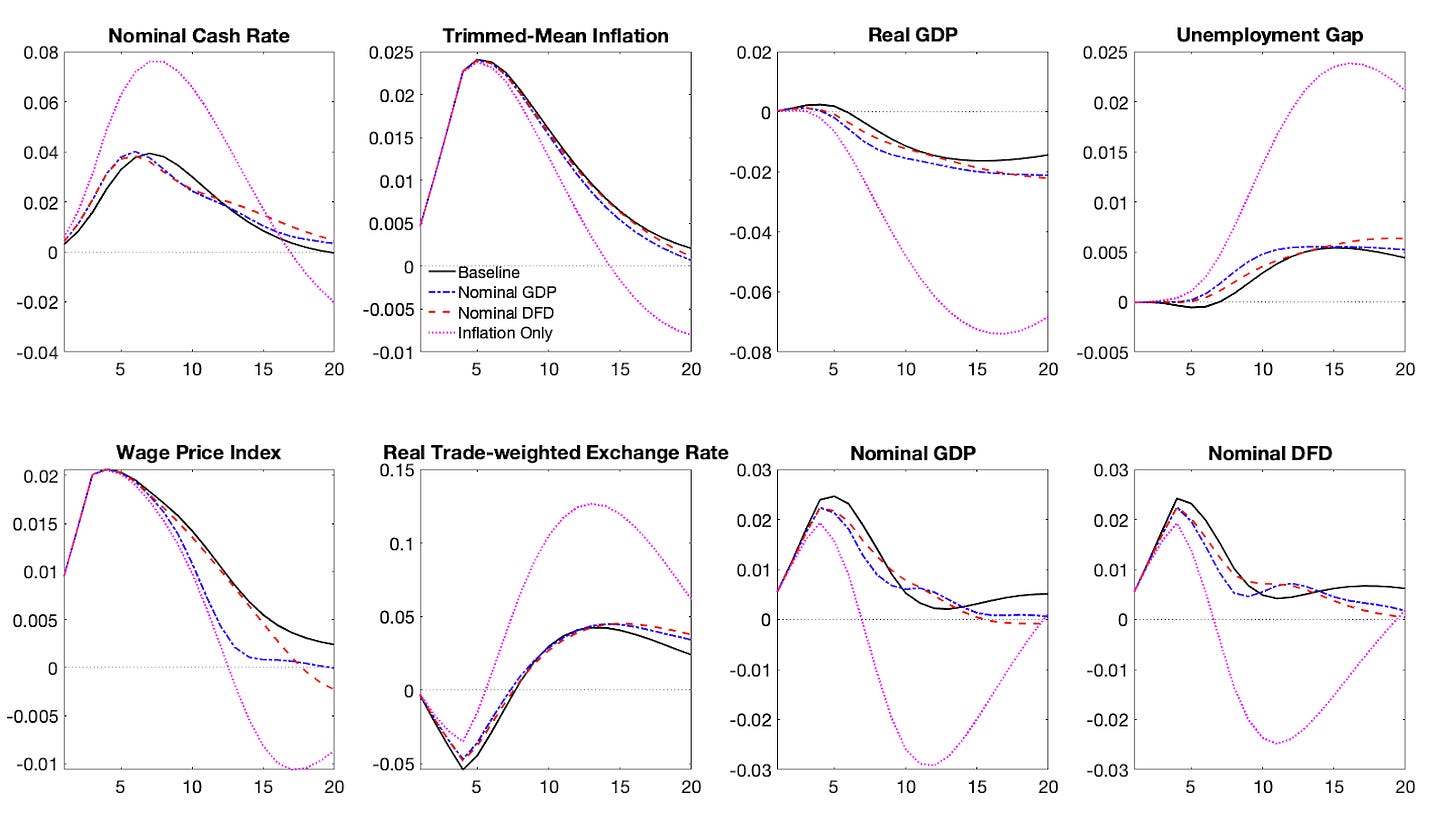

Most noticeably there is now a direct impact on trimmed-mean inflation, with higher food prices feeding directly into a higher core inflation rate. The higher rate of price growth means that now all monetary policy rules call for an increase in the nominal cash rate in response to the rise in food prices.

The size of that increase varies considerably however. Nominal GDP-targeting and inflation targeting call for an increase in the normal cash rate that is far higher than either the baseline calibration or a nominal DFD-target. This more aggressive response leads to a much larger increase in the unemployment rate and a larger deviation of the inflation rate below target in the medium run.

While nominal GDP-targeting seems to engender an unnecessary degree of volatility in the Australian economy, targeting nominal domestic final demand produces results that are largely inline with the status quo - however the unemployment gap lasts for longer under nominal DFD-targeting.

Mark up for what

What about a shock to inflation expectations? This approximates a price markup shock by increasing the inflation rate while decreasing output.

Inflation targeting does aggressively try to lower the impact of a shock to inflation expectations at the cost of higher unemployment and a degree of overshooting. The other three monetary policy rules have quantitatively very similar outcomes to each other with a higher inflation rate being traded off for a smaller increase in unemployment. Any rule that places weight on both inflation and activity seems to produce a similar outcome in response to mark up shocks.

Housing the boom

A housing shock, which boosts rent and house prices, responds much like an aggregate demand shock with higher prices boosting residential investment. This could be interpreted as an increase in demand for housing or perhaps a reduction in supply (perhaps from a natural disaster?). This shock boosts inflation and the labour market under all monetary policy rules.

Pure inflation targeting performs pretty poorly, not responding quickly enough before the economy heats up. Nominal DFD-targeting is probably the best rule out of the alternatives, but the results are generally quite close.

Ultimately this is just one way of considering the optimal targeting rule. An alternative approach (outlined by both Peter Tulip and Warwick McKinnon) is to simulate the model under the various rules and see how macroeconomic outcomes change.

A health warning from your doctor

I have found the inbuilt simulation code in eviews to be somewhat temperamental. Sometimes it manually solves but programmatically fails to converge or vice-versa - perhaps I am just bad at using Eviews. It also produces results that have high levels of volatility and I am not 100% sure why. So I would take these results with a grain of salt. It would be great if the RBA published the code showing how they simulate MARTIN as the Federal Reserve does.

That being said, this table shows how the different policy rules impact the standard deviations of macroeconomic variables.

Health warnings aside, it seems the baseline calibration does a decent job at minimising volatility in inflation and the unemployment gap. Though notably the nominal DFD target does produce a lower level of volatility in GDP growth.

These results suggest to me that the baseline calibration of placing some weight on inflation and some weight on the unemployment gap seems to be the best approach. While this is close to the status quo (indeed it comes directly from a RBA RDP!) the RBA current does not give explicit relative weights to its twin goals of stabilising the currency and full employment. Being explicit about how it weighs the two and how it estimates and updates its view of the NAIRU would be a significant improvement on the status quo!

A more interesting exercise would be to consider how these volatilities might change under a different array of shocks - for example considering a more volatile world due to climate change - but I will leave that exercise for a future post!

Interesting that NDFD targeting lowers NDFD vol, but NGDP targeting raises it. Can you do nominal GLI targeting, ie, put compensation of employees in the reaction fn?