The latest soaring inflation figures have all but locked in another 25 basis point hike when the RBA reconvenes on the 7th of February. But some are asking why the RBA is lifting rates at all when inflation is being driven by supply side effects, such as the war in the Ukraine, Covid supply chain snarls and poor harvests etc. If food and fuel are driving the price level higher, is it really beneficial or fair to lower aggregate spending in response?

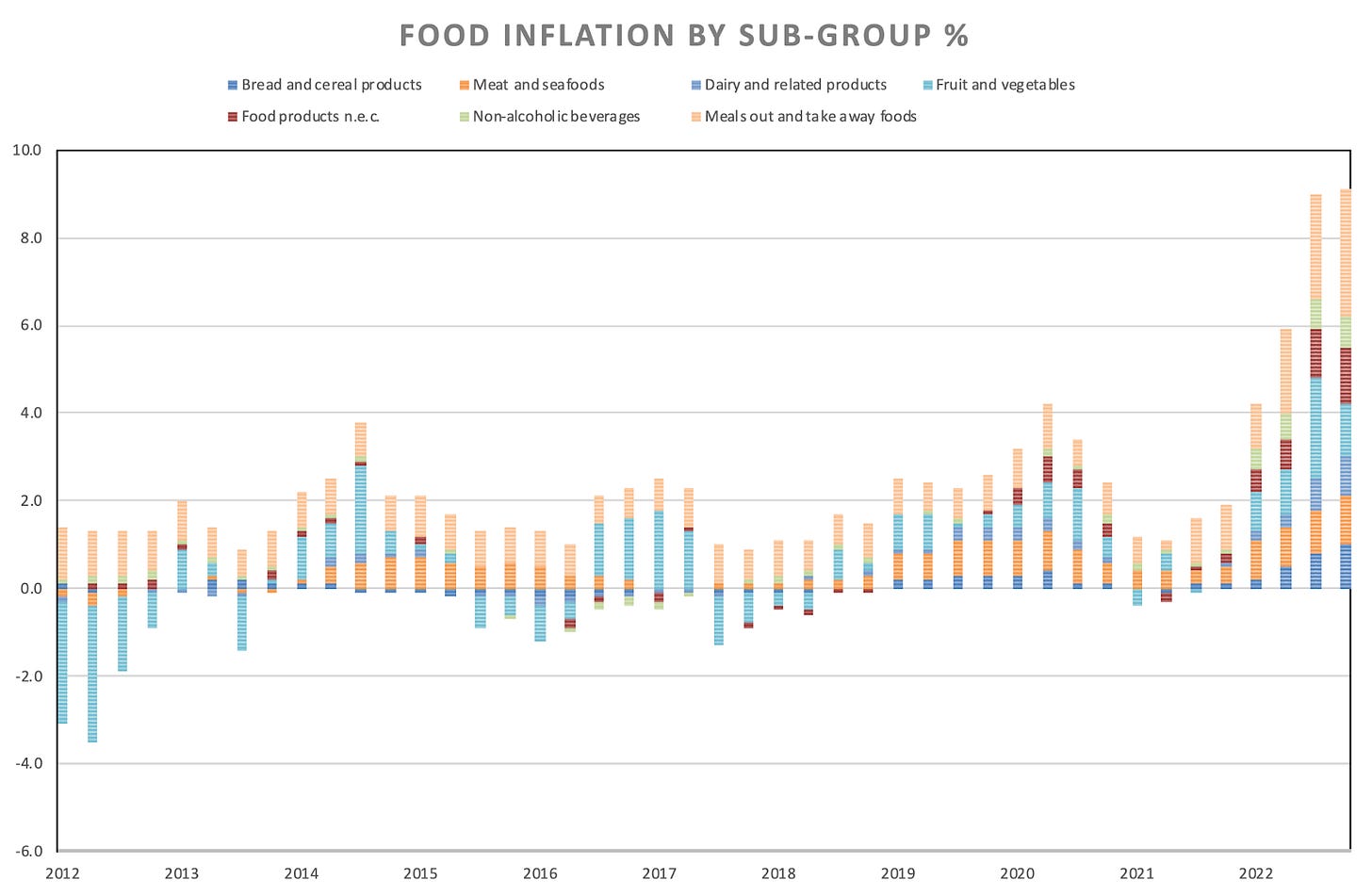

And food inflation is at extremely high levels, increasing by 9.2% over 2022. At first glance this seems like a sector over which households have little discretion and where prices are often dictated by international markets. But this headline figure can be somewhat misleading and when we break down the food inflation rate by its subgroups we see a more nuanced story emerge.

The ingredients of inflation

Ukraine is one of the biggest wheat producers in the world and the invasion has sent its exports plummeting and the price of grains soaring. Consequently bread and cereal products have seen a large increase in price in Australia over 2022, but because they make up a relatively small share of total food consumption the overall impact on the total food index is muted. The biggest contribution was from the meals and take away foods subgroup which was responsible for over a third of the food inflation in 2022.

This matters for two reasons.

First take out food and restaurant meals are much more of a discretionary good compared to eggs or milk from your local supermarket. This is an area in which households can cut back on their consumption, lowering demand and thus helping to reign in inflation. The large increase in the price of eating out has been driven by a variety of factors, but high demand is clearly a big part of the story as the ABS statistics on retail trade make clear.

Secondly, while the price of bread largely reflects the price of the wheat used to make it, restaurant meals reflect a wider set of costs. Producing a meal in a restaurant requires lots of local labour and expensive rent in a popular location. The domestic inputs of labour and rent are much more responsive to changes in the Australian economy (and domestic monetary policy) than international food markets. While monetary policy cannot stop the invasion of Ukraine or conjure up more bushels of wheat, it can lower nominal wages and commercial rents by driving down demand.

A lot of the inflation we have seen in food would have happened no matter what the RBA has or will do. But eating at at Vue du Monde or UberEats-ing a sneaky Nandos is absolutely a part of the economy where we have seen high demand which has contributed to the higher rate of inflation. So while it is true to say that higher food prices have contributed to the current high rate of inflation, it is not just a purely exogenous, supply-side effect from overseas, but in part another sign of an overheated economy for which the answer is higher interest rates.