The lady is for turning

Why the RBA will hike interest rates tomorrow

One of the worst aspects of writing a Substack is the lack of an editor to keep you on the task of churning out content week in, week out. Far too often, I have an amazingly insightful, piping hot take in my drafts folder for weeks before I finally commit to publishing it.

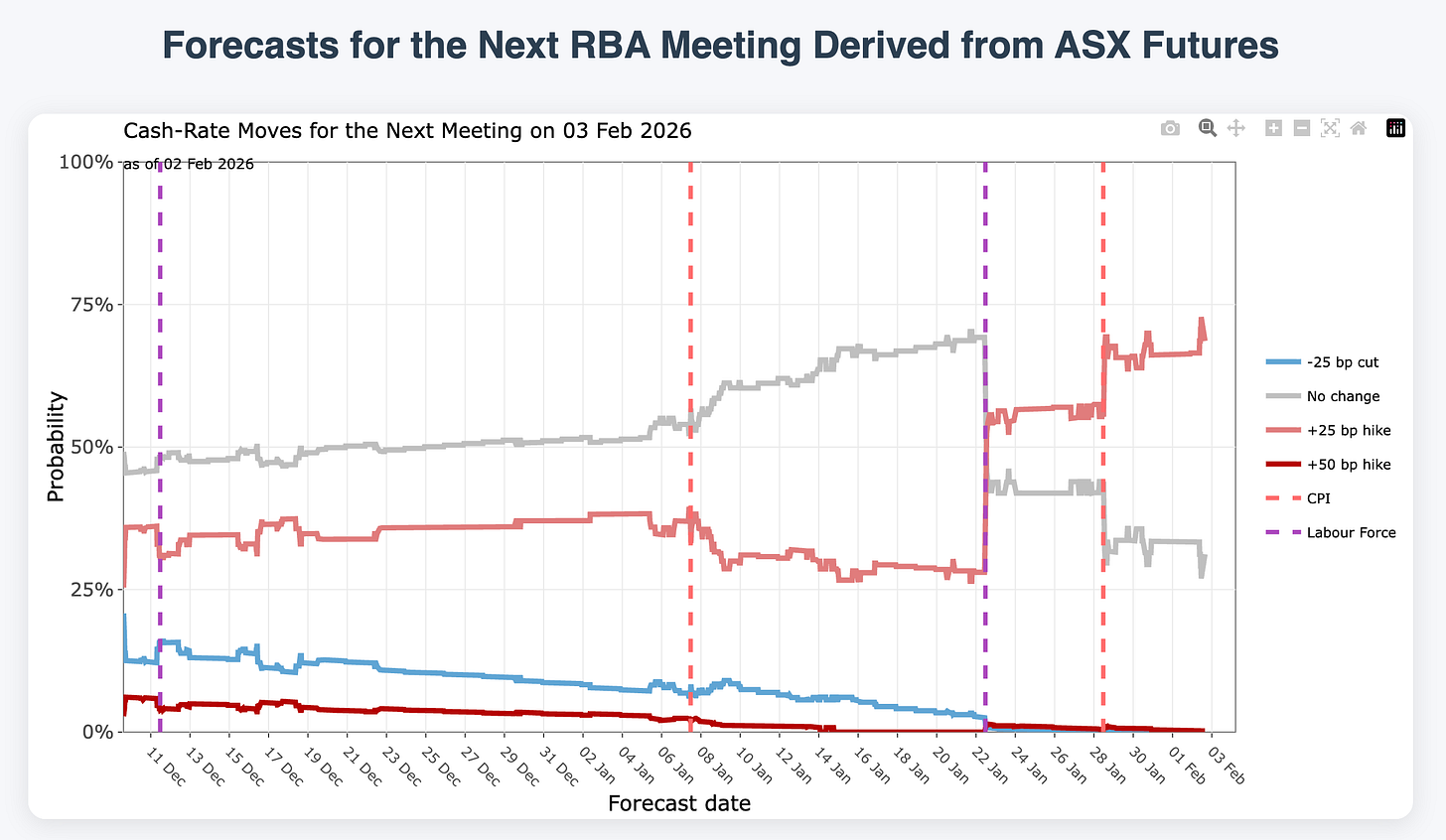

Alas, in the past few weeks it’s proved particularly painful to my ego, as I had long diatribe written about how markets were dramatically underpricing the risk of an interest rate hike when the RBA met in the first week of February. In the meantime, ABS data releases came out that almost perfectly proved my point, so before I could publish, markets finally woke up.

So you’ll just have to take my word for it that my savant-like forecasting ability was on the money.

But honestly, this shouldn’t have been a big surprise.

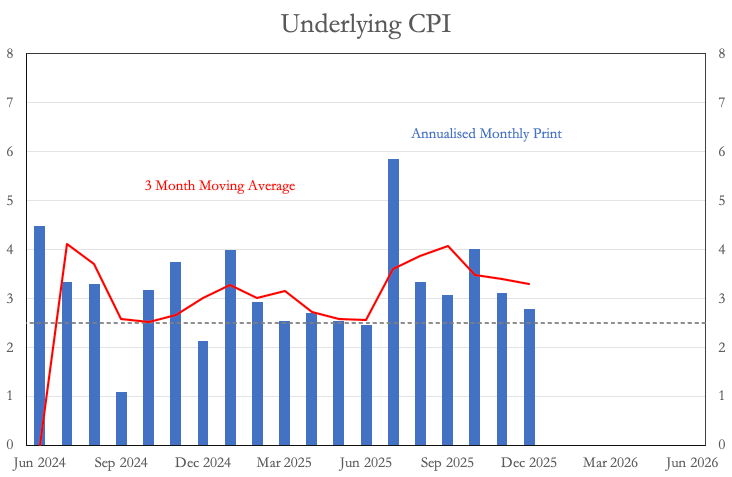

Yes, the unemployment rate ticked down and came in slightly below expectations. But if you looked at the monthly underlying CPI, the December print was, if anything, slightly weaker than the previous couple of months — and yet it still contributed to a hefty 0.9 per cent trimmed mean inflation outcome for the quarter. The writing was on the wall. It just took an ABS press release to wake markets up.

If anything, markets are still too cautious about the RBA. Current pricing implies roughly a 70 per cent chance of a hike. I’d peg it closer to 80 or 90 per cent.

Why?

For the very simple reason that that’s exactly what the data shows.

The strongest argument for the RBA staying put is not about inflation or employment, but about communication. Only a couple of months ago, policymakers were openly debating the prospect of rate cuts. After a long summer break, many Australians might be surprised — and understandably frustrated — to discover their mortgage rates going up again.

But the shift from meetings every four weeks to every six to eight weeks, combined with the RBA’s expanded transparency and press conferences, means these sorts of drawn-out messaging pivots are no longer necessary. The Bank has fewer meetings to waste, but more opportunities to clearly explain its thinking.

And in any case, Michelle Bullock was admirably forthright in the December press conference. Rate cuts were off the table, and hikes in 2026 were explicitly on the table. That’s why I’m confident the RBA will ultimately move.

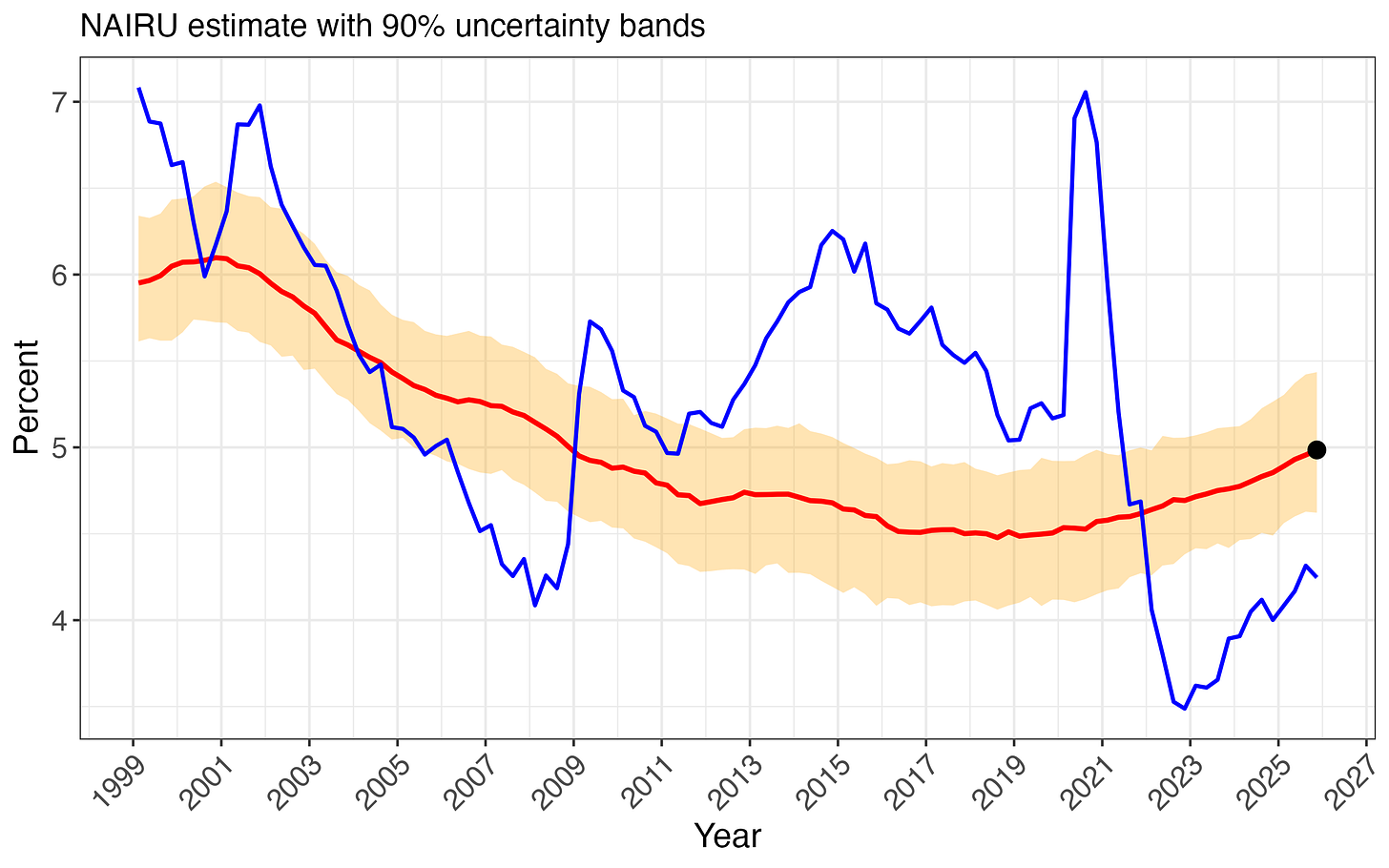

This also helps resolve the paradox that was the combination of a substantial unemployment gap and low inflation. Unfortunately, the recent data suggests the dream of a permanently lower NAIRU was just that — a dream. Australia hasn’t escaped the economic gravity that requires a higher unemployment rate to keep inflation in check.

If anything, my RBA model suggests the NAIRU estimate continues to drift higher, with the post-pandemic inflation burst pointing to a figure almost bang on 5 per cent.

So does this mean the RBA made a mistake by cutting rates late last year?

I don’t think so.

The cuts came well before the current uptick in inflation. At the time of the August meeting on the 12th — when the last cut was delivered — there was strong evidence inflation had returned to target. The first genuinely concerning inflation print was the July monthly CPI release, published on the 27th of August.

In other words, it was plausible at the time that the economy was gliding into a near-perfect soft landing.

For that reason, I think it’s an overreaction to claim this was some ginormous blunder by the Reserve Bank, or that policymakers are now “backflipping”. What actually happened was a prioritisation of hard incoming data over structural labour market models — models that continued to warn that underlying tightness would eventually translate into inflationary pressure.

It’s always tricky when models and real-time data diverge. And while, with the benefit of hindsight, we should have trusted the models more, I think it was a very reasonable call at the time to lean on the observed inflation outcomes.

Yes, in hindsight the models were right. But we’re still dealing with the wash-up of COVID-era shocks, particularly in the labour market. A range of indicators at the time suggested softness that the headline unemployment rate failed to capture. Given that context, it wasn’t unreasonable for the RBA to put more weight on the data in front of them than on structural estimates.

As it turns out, the models were right — and the data has now caught up.

Changing your mind isn’t weakness. In central banking, it’s a form of strength. The first rule is to remain responsive to the data — in both directions. The real failure would be locking yourself into a narrative and refusing to adjust, or waiting unnecessarily long to do so.

Which is precisely why the Reserve Bank of Australia is almost certainly about to hike interest rates tomorrow.

I think focusing on the individual decisions based on the data at the time misses the bigger strategic point.

The RBA was aiming for a risky "narrow path", soft landing. It was deliberately doing only the barest minimum to control inflation. This was always going to be beholden to economic shocks and is just bad strategy in an uncertain world.

Maybe they almost pulled it off - but even if they did that would have been more good luck than good planning. And, most importantly, it's not the way you should run monetary policy. Taking high risk gambles to try and butter the landing is not what prudent central banks should be doing.

Great write-up. We know there are large error-bands with the RBA forecasts so I don’t see anything wrong with when the direction of the data changes adjusting your decision-making.

There were very few people saying the RBA did the wrong thing cutting rates last year, the data said they should and the rest of the world were cutting rates.

It’s only now with hindsight that most people are so confident that they got it wrong.

I don’t see a more volatile interest rate cycle as necessarily a bad thing it will keep people on their toes. People just don’t like it because they became accustomed to constantly falling interest rates over the decade to 2022.