Some economists consider monetary policy to be a somewhat simplistic affair. The only question you need to answer each month is whether the cash rate should be nudged slightly higher or slightly lower. Often central bankers just shrug their shoulders and put off the decision entirely until next month’s meeting, leaving the cash rate unchanged altogether.

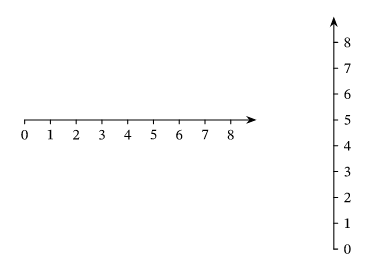

Traditional monetary policy is thus a problem with one dimension - deciding the value the cash rate should be. Each month you could lay out the entire range of outcomes on a single one dimensional number line.

Setting the cash rate is thus far more straightforward than the tricky trilemmas inherent in tax policy or the moralistic welfare judgements involved in where to target government spending. Sometimes it can be hard to determine if the cash rate should rise or fall. But if you get it wrong, e.g. keeping the interest rate too high, thus causing a recession, then the signal extraction problem becomes much easier and you can (in theory) swiftly move to correct the error.

However unconventional monetary policy greatly expands the dimensionality of the central bankers’ problem. Quantitative easing is a much more complex policy with a suite of choices to be made. How many assets should be bought? What assets to buy? Private or public assets? Which lines of Treasury debt? What should be done with these assets as they mature?

Collapsing into a singularity

But with the end of QE monetary policy has collapsed down to a single, zero-dimensional question: When will the RBA lift interest rates from the effective lower bound?

There is no question that interest rates will go any lower (negative interest rates are off the table), the only question of any importance is when will the RBA choose to lincrease from the current rate of approximately zero percent. When will the Board declare that “Lift-off Day” (L-day) has arrived?

Why does all of this matter? Well one reason that central banks prefer not to provide forward guidance for the path of the cash rate is that it is difficult to accurately and succinctly communicate it’s 1-dimensional future path and the associated uncertainty around that estimate. Occasionally banks provide short-lived signals (“the next movement is more likely to be up rather than down”) but they rarely outline their current view on future interest rate movements.

But now when the main question before the RBA Board is what date to declare lift-off that complexity is largely removed. The Governor surely has a date in mind for when lift-off will occur should their current forecasts prove accurate, perhaps even a range of possible dates, and communicating that date to the market each month would be a relatively straight forward message.

Given the apparent disagreement Phil Lowe has with current market pricing the RBA could provide a great deal of clarity simply by providing a current estimate for L-day each month. The markets may not believe the RBA’s forecasts, but by providing a clear connection between how the economy trundles along in 2022 and the dates that L-day is expected ton the RBA could greatly improve the transparency of it’s reaction function and help resolve this apparent confusion.