Today’s CPI figures will play a key role in determining whether and when the RBA begins cutting interest rates. Much attention will be on the trimmed mean inflation rate. However, a recent twist complicates inflation analysis: the government’s cost-of-living measures have lowered the CPI, either coincidentally or by design.

This has led to steep falls in the headline inflation rate. At least so far, the impact on underlying measures, such as the trimmed mean inflation rate, seems to have been muted.

So are the trimmed-mean figures still a reasonable estimate of the underlying inflation rate? Cards on the table, while I was previously confident in the reliability of the trimmed-mean rate I have changed my mind.

When the facts change…

To test the reliability of the trimmed-mean measure I ran a short simulation exercise using historical data from CPI subgroups—the ABS categories of goods from which the trimmed-mean and weighted median are calculated—I examined how these underlying measures would change if the government lowered the price growth of one of the 87 subgroups via a subsidy and compared it with the impact on headline inflation.1

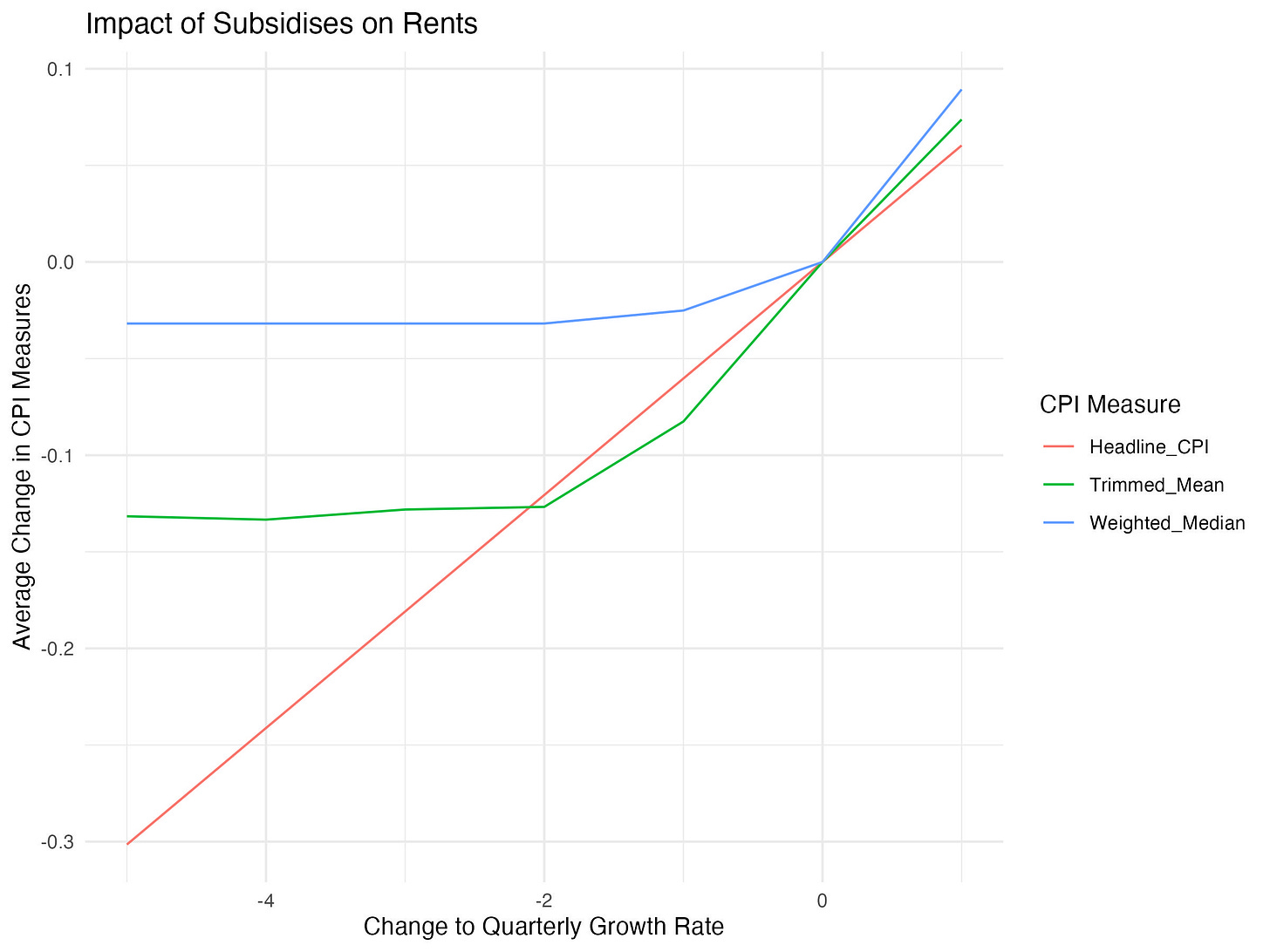

One of the biggest subsidies has been the increase in Commonwealth Rent Assistance which has lowered the annual growth in rents by around 2 percentage points. So what is the average effect of a reduction in rental inflation rate on the three main CPI measures: headline, trimmed-mean and the weighted median?

The effects on the headline measure are predictably uniform: as the impact of the subsidy increases, the effect on the headline rate of inflation scales up linearly. For example, if quarterly rent inflation is 5 percentage points lower than it otherwise would have been, and rents make up approximately 6% of the consumption basket, the headline inflation rate would be about 0.3 percentage points lower—a significant decrease for a quarterly number.

But what about the underlying measures? For a large decrease in rental inflation, the trimmed mean inflation rate decreases by only 0.13 percentage points on average—about 40 % the size of the headline CPI decrease, smaller but still substantial. This smaller effect occurs because a large price decrease often shifts rental inflation into the lower end of the price distribution, where it gets trimmed out. Nonetheless, even with a substantial reduction rental inflation remains in the middle 70% of price changes and impacts the trimmed mean quite often. Even if it does get trimmed out it pushes some other low-inflation subgroup into the non-trimmed middle portion of the distribution which will lower the trimmed-mean inflation rate.

It gets worse!

What’s most interesting is that the effect on the trimmed mean is decidedly non-linear. If there’s only a small 1 percentage point decrease in rental inflation, the effect on the trimmed mean inflation rate can actually be larger than on the headline CPI. How is this possible? Rental inflation tends to have low volatility, keeping it within the middle 70% of price changes most of the time. If you implement a small subsidy to rents then it is still fairly likely that the subgroup will remain within the middle part of the distribution.

If the lower rental inflation is not trimmed out however, it will have a larger weight in the trimmed-mean measure (6% divided by the 70% of prices remaining) than the headline (6% divided by the 100% of prices included in the total CPI)!!

This creates an intriguing statistical artifact. If your goal were to influence the trimmed-mean inflation rate, you would be better off implementing a broad series of small subsidies to goods you were confident were going to be in the middle of the distribution. These small changes are more likely to keep subsidized goods within the middle 70% of price changes, ensuring they affect the trimmed mean, without being so large as to get trimmed out.

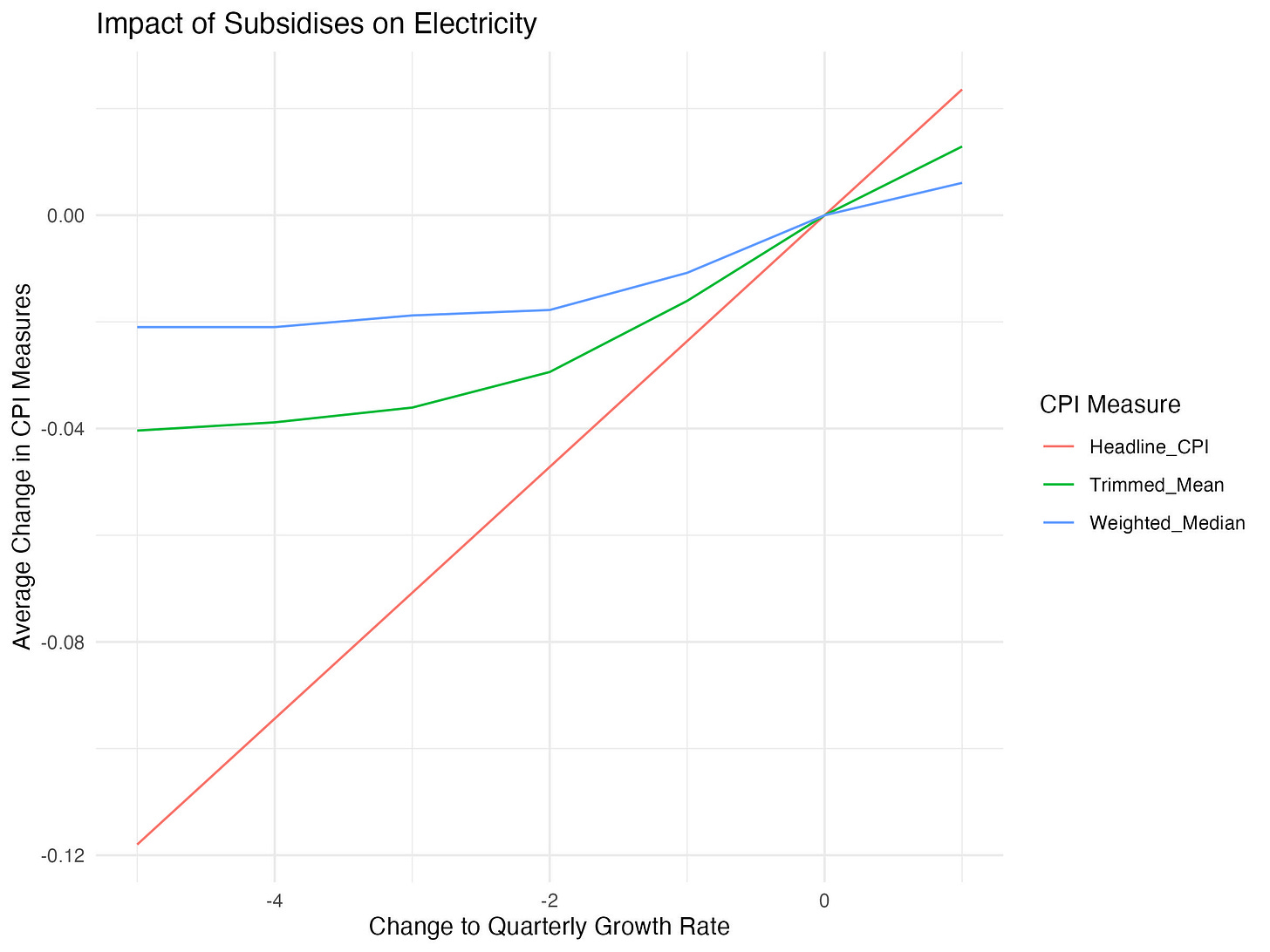

However, this result is not consistent. Take for example electricity prices which are much more volatile and frequently removed by the trimmed mean measure. Subsidies to electricity have a substantial impact on headline CPI but a relatively small effect on the trimmed mean.

It’s also worth noting that these are average effects over the past decade of inflation data. While rent is usually in the middle 70%, and electricity prices are often trimmed-out this may not be the case for the specific price changes of Q4 2024. Since most of the subsidies are targeting prices that are growing quickly we might expect the impact on the underlying inflation rates to be a little larger than if they were deployed randomly.

Median matters

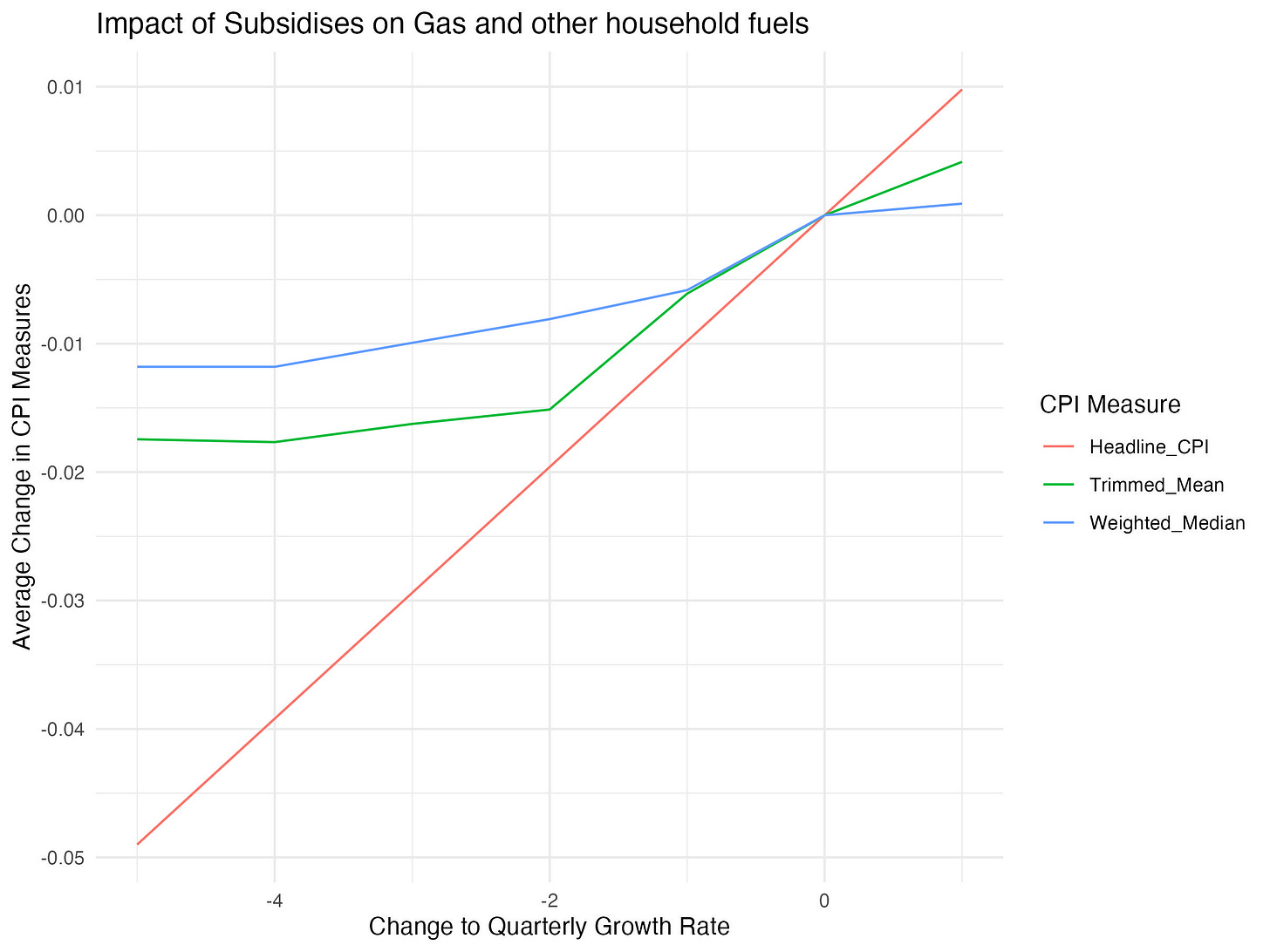

Among all measures the weighted median is least affected by subsidies - a fairly consistent and significant result. By its design, the weighted median represents the price change at the midpoint of the distribution. Half the time a subsidy will have no effect on the median as it merely lowers a price that is already below the midpoint. Even when it does affect the median, the impact is small, as the central part of the price distribution is dense, making the median resistant to small shifts.

If you’re concerned about the potential “juking” of inflation statistics through cost-of-living subsidies, pay more attention to the weighted median than the traditional trimmed mean inflation rate that the RBA and economists often rely on. The weighted median is a much harder statistic to manipulate and provides a clearer picture of underlying inflation trends. As the quarterly CPI figures come out, this will be the measure to watch for hints on whether the RBA will cut interest rates at their next meeting in February.

Post Credit Charts

I used data going back to 2011 when there was some changes in the subgroups, and was a bit lazy and only used subgroups at the national level.