Counting the Cost of the Great Undershooting

Counterfactuals part II

While the RBA’s use of monetary policy was effectively used to ward off recessions in 2001 and 2008. The counterfactual results for 2016-2019 tell a different story.

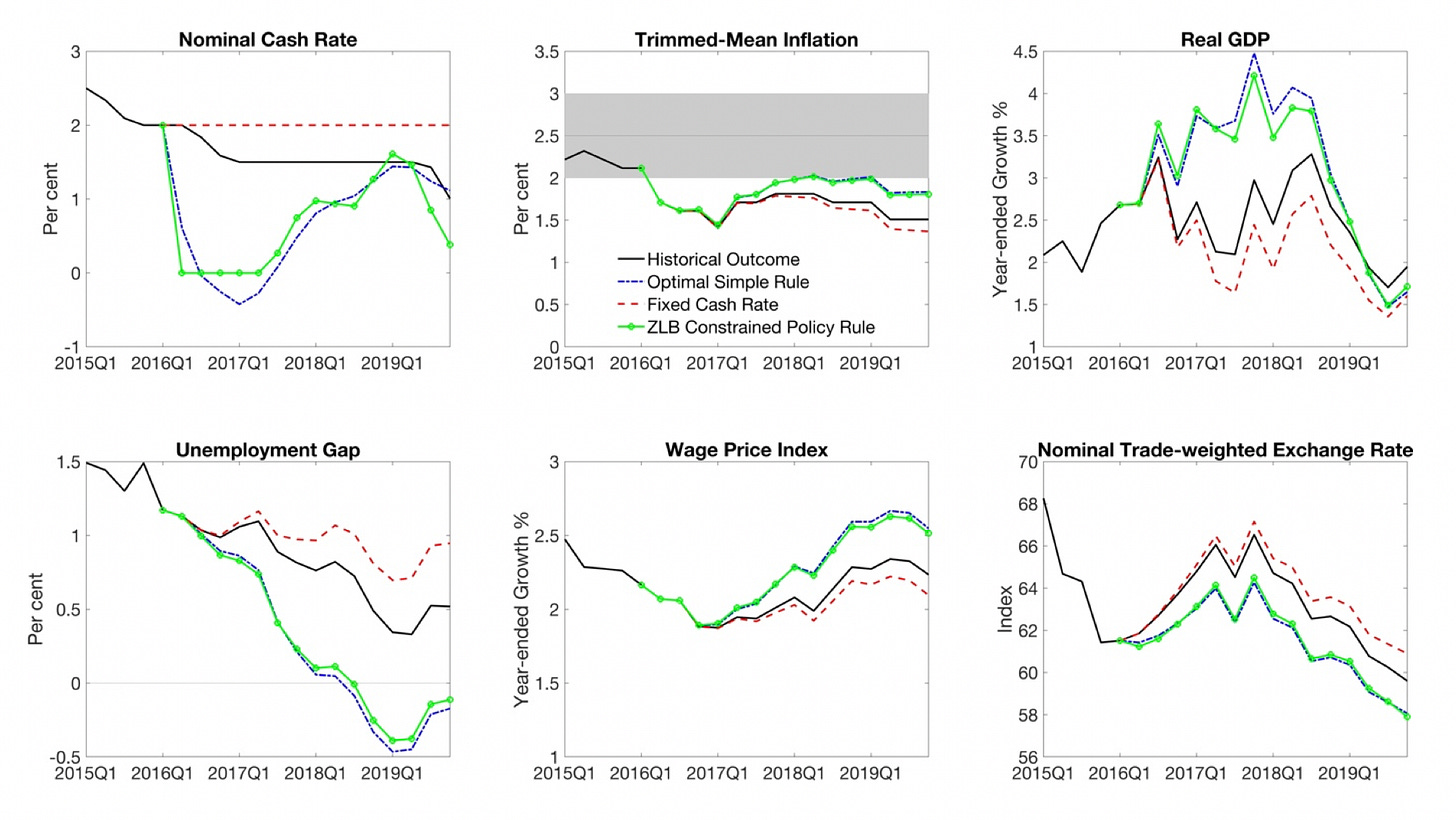

The third historical episode I examine is the period of below target inflation that occurred from 2016 up until the end of 2019. Over this period trimmed-mean inflation was consistently below the RBA’s target band averaging only 1.7 per cent. At the same time a significant unemployment gap opened up starting at over 1 percentage point before falling to 0.5 percentage points at the end of 2019.

In response to this period of low inflation and high unemployment the cash rate was kept largely constant with the cash rate decreasing only 50 basis points until the middle of 2019, when it was lowered a further 75 basis points.

By contrast the ‘Optimal Simple Rule’ counterfactual (whether optimised over the counterfactual period or the full sample) outlines a radically different path for the cash rate. The optimal simple rule calls for a large decline in the cash rate over the sample period. This is because the combination of low inflation and a large unemployment gap can both be simultaneously ameliorated by easing monetary policy.

However, the cash rate target is generally not able to be set at negative values and is instead subject to an effective lower bound of zero per cent. While a negative cash rate could be interpreted as the use of unconventional monetary policy measures, such as quantitative easing, I also estimate a counterfactual in which the zero lower bound is a binding constraint. In this counterfactual the RBA chooses the optimal number of periods to hold the cash rate at 0 per cent before reverting to the policy rule.

Compared with a hypothetical in which the cash rate was kept unchanged, I estimate that monetary policy led to 0.9 fewer percentage point-years of unemployment. However, had monetary policy followed the optimal simple rule it would have saved 3.0 percentage point-years of unemployment. If I use a counterfactual in which the zero lower bound operates as a binding constraint we find that optimal monetary policy would have saved 2.9 percentage point-years of unemployment.

In either case, this translates into a significant number of jobs. The average size of the labour force in 2016-2019 was 13.1 million people, and the difference between actual outcomes and the optimal simple rule was 2.1 percentage point years of unemployment (or 2.0 if the zero lower bound was a binding constraint). The failure to implement optimal monetary policy thus cost the equivalent of approximately 270,000 people being out of work for a year.

270,000 jobs is a big deal. By comparison the suburban rail loop in Melbourne is estimated to employ only 8,000 jobs when construction starts on the first stage, the inland rail project is estimate to create around 20,000 jobs1. Closing Australia’s border is estimated to have cost around 72,000 jobs. Alternatively we could shut down the coal mining industry tomorrow and it would directly affect only 38,100 jobs! All of these examples are massive public projects or policy decisions, but they are dwarfed by the RBA’s decision to run the economy to slow over that four year period.

The monetary policies pursued in 2016-2019 were a substantial error by the RBA.

What caused it?

I think we can reject the explanation that monetary policy was optimally responding to changes in fiscal policy. In fact, fiscal policy tightened over this period, with federal payments falling from 25.5 per cent of GDP in 2015-16 to 24.9 per cent in 2016-17 and 24.5 per cent in 2017-18 and 2018-19. This contraction in fiscal policy should, if anything, have encouraged looser monetary policy.

Another explanation is that the central bank was overly optimistic about wage growth. In every year from 2011 to 2019, the RBA forecast a higher level of wage growth than actually occurred. Over a one-year forecast horizon, the error was around one quarter of a percentage point. Over a two-year forecast horizon, the error was around one half a percentage point.

Another potential explanation was a concern that a lower cash rate would send a signal that the RBA expected demand to remain weak and would thus lead to a decline in business and consumer confidence. This concern was specifically cited by the RBA as a reason why the bank did not decrease nominal interest rates in 2019. However, this view conflicts with RBA research (He 2021) which concludes there is little evidence for such an “information effect” being caused by changes in the RBA’s cash rate.

But most likely explanation is that the RBA refused to cut interest rates as they were overly concerned about house prices. As the September 2017 RBA board minutes stated ‘Taking into account all of the available information, and the need to balance the risks associated with high household debt in a low-inflation environment, the Board judged that holding the stance of monetary policy unchanged would be consistent with sustainable growth in the economy and achieving the inflation target over time.’

Similarly, Governor Philip Lowe stated in a 2017 speech, ‘We would like the economy to grow a bit more. If we were to try to achieve that through monetary policy that would encourage people to borrow more and it would probably put upward pressure on housing prices. At the moment I don’t think those two things are in the national interest.’

This approach of ‘leaning against the wind’, has generally been found to fail any reasonable cost-benefit test (Svensson 2017; Habermeier et al 2015, Gorea, Kryvtsov and Takamura 2016; Kockerols and Kok 2019).

Indeed, the RBA’s own researchers have estimated that the costs of leaning against the wind are three to eight times larger than the benefit of avoiding financial crises (Saunders and Tulip 2019)!

It is a shame then that at the most recent parliamentary testimony Governor Lowe didn’t take the opportunity to discuss previous policy errors such as these when asked by the House Committee. The best way to avoid repeating mistakes is to acknowledge, diagnose and analyse them. Hopefully counterfactual analyses such as these can illuminate where such errors have occurred in the past, so that central bankers can do better in the future.

Including a wishy-washy estimate of indirect jobs created.