The Reserve Bank of Australia recently released a fascinating research discussion paper1 exploring the impact of investment tax breaks on business behaviour. Authored by Nu Nu Win, Jonathan Hambur, and Robert Breunig, the paper digs into how various tax incentives over the past two decades affected firm-level investment.

Using data from the ABS Capital Expenditure (CAPEX) survey, the researchers evaluate a broad set of tax credits and how they affected actual investment spending.

Surprisingly, the study finds that most of these investment tax incentives had no statistically significant impact on business investment. In particular the instant asset write-offs that have been rolled out for small and medium businesses seem to have little measured impact at all.

What makes the study particularly powerful is its use of policy thresholds and it’s analysis of half a dozen different investment incentives. Most of these investment incentives are available only to firms under a certain revenue cap—ranging from $2 million to $5 billion—allowing for a "regression discontinuity" style approach. That is, by comparing firms just above and just below the threshold, the authors can credibly estimate the marginal impact of the policy.

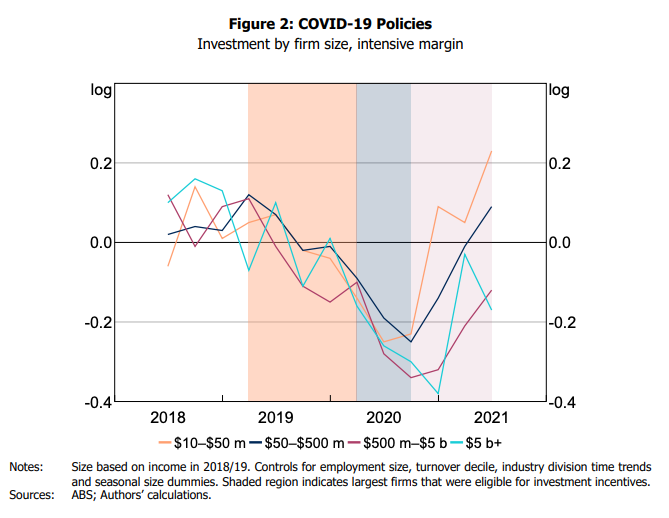

While the authors provide detailed regression results, the headline results can be seen in the figures below. The green line shows the investment outcomes for firms that were (just) eligible for the instant asset write off, while purple shows the outcome for firms that were not.

If you can see clear evidence of the green lines soaring higher relative to the purple ones you have a better imagination than me!

What works

The only policy that showed a significant and positive effect was the bonus deduction program implemented during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

Why was this the exception?

The GFC bonus deduction was larger in terms of the benefits. An instant asset write off is like a free loan from your future self. Beneficial but you do have to pay yourself back. A bonus deduction represents additional money from the Commonwealth Treasury which is much more likely to motivate firms.

It was temporary, which likely added urgency. Firms had to invest quickly to benefit, creating a strong time-based incentive.

Credit markets were tight, making the cashflow boost from accelerated deductions far more valuable. Firms facing credit constraints were more likely to respond to a policy that helped replenish their balance sheets.

Interestingly, this same pattern didn’t hold during the COVID-19 period, despite the availability of similarly generous write-offs, including full expensing in some cases. During COVID, firms of all sizes appeared to follow similar investment trajectories, regardless of eligibility. Even temporary, uncapped full expensing policies failed to generate a noticeable change in investment by medium and large firms.

Instant asset write-offs seem to be poor tools for boosting investment in normal times. While they may offer some minor, hard-to-measure benefits, they are expensive and add complexity to the tax system without delivering clear results. They might slightly improve business cash flow, but they don't seem to spur meaningful new investment.

However, if the investment subsidy is generous enough, time-limited, and deployed during a genuine credit crunch, it may work. The GFC-era policy is the standout example: its scale, urgency, and timing aligned in a way that seemed to deliver genuine investment gains.

As a result, policymakers should think twice before relying on these tools as standard levers for investment stimulation. Though that hasn’t stopped the Coalition promising to bring it back if they win the up coming election.

Post script

Although not the main focus of the paper, the authors also explore the effect of corporate tax cuts on investment, with more promising results.

During the 2015 small business tax cut, investment in buildings and structures by eligible firms jumped by 66–83%, a surprisingly large response to a relatively modest rate change.

In 2016, another cut—accompanied by a threshold increase—had a more modest but still plausible 20–30% boost to investment.

These results suggest that lowering the ongoing tax burden may be more effective at driving real capital expenditure than short-term write-off programs.

Though 2 of the 3 authors are affiliated full time with ANU.